I’m cooking something new for dinner tonight. I came across a recipe for sajiyeh that looks tasty. So I’m giving it a try. The recipe says it will take 40 minutes. That seems reasonable. And in my experience, most recipe estimates are pretty good. I usually take a little longer than they say, but I attribute that to my slowness rather than an error in the recipe.

I find it useful when a recipe includes an estimate of how long it will take. It gives me valuable information about how difficult the recipe is likely to be (and how many dishes I have to wash when I’m done).

I don’t find it useful, however, when a boss or client tells my agile team how long something will take. In fact, when product owners or project managers tell me how long something should take or they provide a deadline, my first instinct is often to reject their estimate, even if the estimate is higher than my own would have been.

The Problem with One-Way Plans

One-way planning, whether it comes from the top-down or the bottom-up, is not ideal. In fact, it works against an organization becoming agile. Bosses, product owners, and clients should not tell a team when something will be done. Similarly, though, a team should not dictate dates without consideration for what the business or client needs.

For an organization to be agile, collaborative planning must be the norm. Creation of the plan may be guided by either the development group or the business stakeholders. But the plan should not be called done until the other side’s input has been considered, often resulting in changes to the plan.

Team-Lead Collaborative Planning

A team may create a high-level release plan describing what will be delivered and by when, based on its estimates of the effort required. But that plan may not suffice to meet the organization’s needs. The business might have very real deadlines. Sometimes these deadlines are so critical that the project itself makes no sense if it cannot be delivered on time.

When project plans and project needs conflict, the developers and business stakeholders should review the plans together and negotiate a better solution.

This does not mean stakeholders can reject a plan and force the developers to deliver more, deliver sooner, or both. It means that both parties seek a better alternative than the one in the initial plan. That may mean

- a later date with more features

- an earlier date with fewer features

- additional team members

- relaxing a particular requirement that had an outsized impact on the schedule

These same options should be considered when a team tells stakeholders that what they’ve asked for is impossible.

3 Ways to Ensure Collaboration

Collaborative planning exists when the organization exhibits three characteristics.

First, plans are based on data and experience rather than hope. When data shows that a team’s historical velocity has been within, let’s say, 20–30 points per iteration, stakeholders cannot insist that a plan be based on a velocity of 40. Everyone involved, including developers, may hope for 40, but the plan needs to be based on facts.

Second, stakeholders need to be comfortable with plans that are occasionally expressed as ranges. Just as in the discussion of velocity above, the most accurate agile estimations use ranges. A team may, for example, promise to deliver by a prescribed date but will retain flexibility in how much they promise to deliver by then.

A third characteristic of organizations successfully engaging in collaborative planning is that plans are updated as more is learned. Maybe an initial estimate of velocity has turned out wrong. Or perhaps a new team member was added (or removed). Maybe the team learns that certain types of work were over- or under-estimated.

In each of these cases, recognize that the plan is based on outdated, bad information until it is updated to reflect new information.

Things to Try

If collaborative planning is not the norm in your organization, there are some first steps that will improve things. First, make sure that no plan is ever shared before both the team and its stakeholders agree. Both sides of the development equation need to understand the importance of creating plans together.

You should also establish a precedent that plans will be based on agile estimates, meaning estimates provided by those who will do the work. No one likes to be told how long it will take to do something—except perhaps in the case of trying a new recipe.

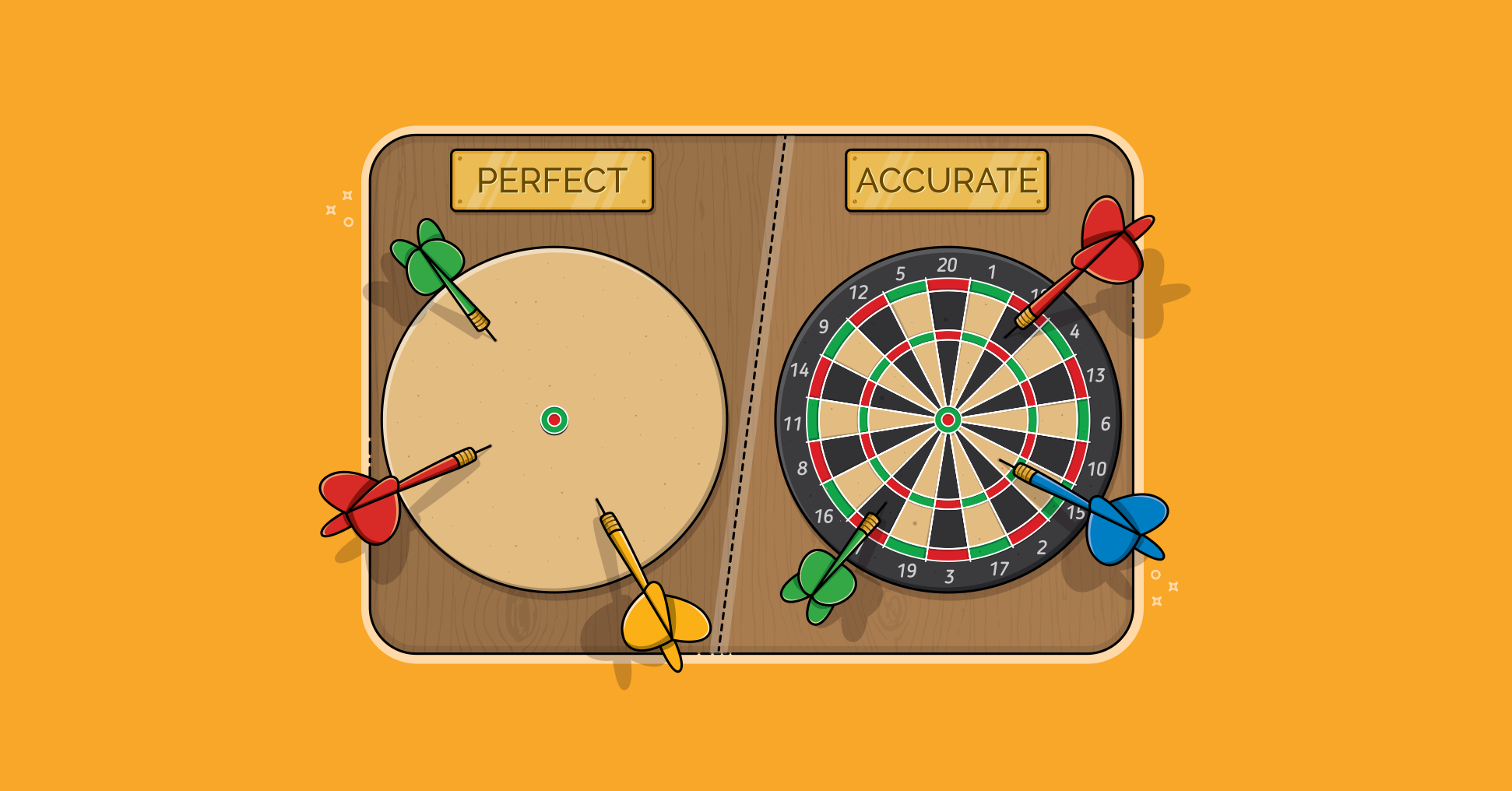

Additionally, speak with stakeholders about the importance of plans being accurate, even at the expense of precision. It seems human nature to favor precision. I recently scheduled a doctor appointment for 1:25 P.M. My doctor has apparently decided his appointments should all be 25 minutes long, yet he’s never once been on time for an appointment.

Similarly, my $29 scale is precise to the tenth of a pound, yet it often differs by half a pound if I weigh myself twice.

Agile teams and their stakeholders also instinctively love precision. Statements like “in seven sprints we will deliver 161 story points” sounds gloriously precise. A team that can so precisely know how much it will deliver must be well informed and highly attuned to its capabilities.

Or team members multiplied a velocity of 23 by 7 sprints, got 161, and shared that as their plan. Precise, yes. But very likely precisely wrong. What if the team delivers only 160 points in seven sprints? Do stakeholders in that case have the right to be disappointed by the missing one point? Perhaps they do, since the team conveyed 161 as a certainty.

Everyone, stakeholders and team members alike, would have been far better served if the team had conveyed its estimate as a range. A more accurate plan might have stated that the team would deliver between 140 and 180.

Collaborative planning combines the wisdom of those who will do the work with stakeholders’ knowledge of where the project has wiggle room. Plans created collaboratively are more likely to be embraced by everyone. And a shared interest in the accuracy and feasibility of the plan means it is far more likely to be achieved.

Last update: December 19th, 2024