In this article I want to focus on using the scrum process and user stories to help scale down a project. I have spent my career growing software teams and building successful (usually!) software products. While at my last company, let’s call them Cosmodemonic Biotech, I helped them grow from forty to over a hundred developers in just three months. We successfully transitioned a legacy product onto a new Java-based architecture. We even had a $130 million IPO. We were as successful as we could be—except that we didn’t have more than a handful of customers for our product, which was something everyone overlooked on our way to that IPO.

In October 2001, we were caught by the dot-com implosion. The $130 million we’d raised in our IPO was both a blessing and a curse. It was nice because with a monthly burn rate of less than $1 million, we were at no risk of going under; however, it also posed a problem because investors clearly expected big things of us and we couldn’t deliver. A small business generating $5 to $10 million in software revenue was not what investors wanted when they invested $130 million in Cosmodemonic Biotech.

Our solution was to gear the company for sale, which would include a drastic reduction in staff. My job changed radically: No longer was I building teams and products—now I was helping to dismantle them. I had to help scale our team down to only twelve people; the first seventy-five jobs were cut immediately, and the remaining thirteen were cut two months later. Instead of helping that team build great software, I had to help them position the company’s main product as a desirable acquisition for another company. I learned a lot in the process— most of which applies to growing teams and building products, not just to shrinking them. This is an account of how I used the scrum process and user stories.

Scrum Process - A Requirement to Simplify

With only twelve developers (eight in programming and four in QA), we knew we’d have to simplify things. Gone were such technical complexities as support for multi-terabyte databases and multiple application servers. Gone, too, was an overly complicated HTML and JavaScript client. If we had any chance of success with the much smaller staff, we would have to rewrite the client in Java and Swing.

We felt we could do this very quickly; however, we were concerned that we might miss an important requirement in doing so. Unfortunately, we had dropped in size so quickly and so unexpectedly, that it was difficult for the survivors to pick up the work and understand the requirements as they rewrote the client. We couldn’t ask the product specification group—they had been completely eliminated. Similarly, there was no way we could read the use cases—they were out of date and far too verbose.

Our solution was to rely on the manual test cases our QA group had written. We’d had a very good QA group who had documented hundreds of tests. We reasoned that our rewritten client would meet all the requirements (buried somewhere in the vast pile of use cases) if it passed all of the tests that were not tied directly to the browser-based interface.

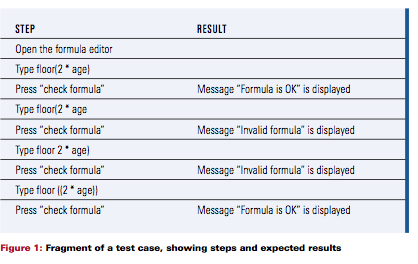

We couldn’t just print out the manual test cases and hand those to the programmers, however, because the test cases were just as detailed as the use cases. The testers had written their test cases by the book. Each test case was composed of test steps, each of which included an expected result. For example, the system included a formula editor into which the user could enter fairly simple formulas such as “floor(2 * Age).” (A fragment of the test case for this is shown in Figure 1.)

There were two problems with this: First, the tests were unnecessarily tied to the user interface; and, second, you had to read many steps to see what was being tested. Our solution was to take these detailed test cases and move them up a level so that they became user stories: brief descriptions of the system’s behavior from the user’s perspective. The partial test shown in Figure 1 turned into the story “user can add parentheses to a formula.” Some detail was intentionally left out of the stories. If the effort to document details (and more importantly, read those details multiple times) outweighed the benefit of having the details, we chose not to document the details. We wanted to avoid ending up with just another variation of the overly verbose use cases we already had. We considered “user can add parentheses to formula” to be sufficient and did not add details such as “left and right parenthesis have to match,” and “parentheses can be nested.” This allowed us to take 3,000 pages of use cases and capture them as fewer than 1,500 stories, with each story contained on one line of an Excel spreadsheet.

INFO TO GO

- Use the simplest set of technologies that will support your application.

- Write user stories as a lighter-weight approach to documenting requirements

- Use the Scrum process to accelerate the project and keep everyone on the same page.

Scrum Process - Daily Activities

Day-to-day existence on this project was surprisingly good, considering that 90% of the company was gone and those who remained were most likely headed for the same fate. Much of this was because we adopted the Scrum process, which empowered the remaining team and helped isolate them from much of the turmoil of the effort to sell the company (see sidebar).

Among our staff of twelve were four of the original testers. Their main responsibility during this time was the conversion of detailed test cases into the user stories we used as requirements. When a tester finished writing the stories for a functional area, he or she would then test the application to see if the stories had already been implemented. Because we were only rewriting the user interface and because our middle tier had been mostly completed, a large number of stories were already working or close to it. I collected the stories and tracked them in an Excel spreadsheet, using colors to indicate stories that were done, unknown, or in process.

While the testers were generating the user stories, the programmers were implementing them. Each programmer chose the stories he wanted to implement and would typically select a block of five to twenty related stories. When he finished coding the stories, a tester would test them. Testing would find the typical assortment of bugs, but testers were also looking for stories that had been missed by the programmer. Because the testers were busy distilling use cases into testable user stories, they were able to spend only about half of each day doing hands-on testing. One of the challenges was balancing their time between writing the stories and doing hands-on testing. I tended to err in favor of writing stories, because I considered their implicit application knowledge less replaceable than some early project user interface testing.

Scrum Process - Transitioning

A few months after instituting these changes, we successfully sold the company. The steps we had taken as we scaled down were invaluable at this point. Had a small company attempted to acquire the project when it had thousands of pages of use cases, test cases, and an overly complex collection of technologies, they would have turned and run. However, by adopting the Scrum process and simplifying everything about our day-to-day work, we had successfully streamlined the project. The acquiring company got a software product that was nearly complete and already passing the majority of the user stories/test cases. They also got a team that had proven itself through incredible adversity, and that had found a highly efficient and agile way of working together.

The acquiring company eventually scaled the team down to four developers, and with a few more months of work the product was successfully released. The Scrum process and the use of simplified user stories were so successful on this project that the acquiring company began to use them on their other projects.

While it is never fun to reduce the staff on a project by over 96%, the techniques we applied on this project helped us succeed during a difficult time. By simplifying our requirements into user stories rather than lengthy use cases and test cases, we were able to streamline the development process and move more quickly. Testers and developers spent more time talking with each other than they had before the rapid downsizing. This was reinforced by our use of the Scrum process and by the need to talk about the stories, rather than rely on the more detailed use cases. Many of the tactics we took when the project’s survival was at stake would serve most projects well throughout our lives.

Last update: January 7th, 2022