By the time an iteration begins, the user stories selected for the iteration need to be small enough that each can be completed within the iteration. This makes splitting stories an important skill for every agile team.

Yet I suspect we’ve all struggled with splitting stories at some point. Many of those struggles result from a common set of mistakes. In this post I’ll address five of the most common story-splitting mistakes and will offer advice on how to stop making them.

#1. Treating Story Splitting as Just the Job of the Product Owner

At the top of my list of common problems is treating story splitting as something for the product owner to do alone. When a product owner splits stories alone, it is quite likely that the new substories will not be split in a very useful way.

For example, since most product owners have little or no technical background, a product owner might split a user story into five substories but leave 99% of the work in just one of the stories. Splitting a story in that way is not helpful. Similarly, without a technical background, a product owner might create new substories with dependencies between them that prevent truly completing any within a single iteration.

While splitting should not be viewed as solely the responsibility of the product owner, the product owner should be involved in splitting. The responsibility should not be given over to the development team alone. For stories to be split in an optimal way, the product owner does need to be involved.

This means story splitting should be viewed as a whole-team activity. That doesn’t mean the whole team has to be involved in every split. Rather it means that splitting isn’t delegated to one or two people on the team who do it for every story.

Instead two teammates may join with the product owner to split a story or two. Later another team member and I might help the product owner split the next story.

My preference is for splitting to be discussed in a daily scrum. The product owner may show up, for example, and announce the need to split 3 stories in the next day or two in preparation for the next sprint. A few developers indicate they’re available to help and a time is chosen right then during the daily scrum.

#2. Splitting Stories along Technical Boundaries

While I coach teams to solicit help from the development team in splitting, doing so can lead to our second problem: splitting stories along technical rather than functional boundaries. You’ve probably seen stories that suffer from this problem. Often these are the stories that get written as, “As a programmer, I want…” and describe functionality from the viewpoint of the team rather of an end user or stakeholder.

Splitting along technical boundaries can lead to stories like:

- As a user, I want a backend that does such-and-such

- As a user, I want a frontend that does the same such-and-such

A good story is one that goes through an entire technology stack. Or at least as much of that technology stack as is needed to deliver the feature. Stories split along technical boundaries gives us stories that don’t deliver any value to users on their own. A frontend (say, a web interface) does users no good until it is paired with a backend (a middle tier and/or database).

To avoid falling into the trap of splitting a story along technical boundaries, see if you can instead split the story based on the paths through the story.

To split a story on its paths, think about the paths through the code the team will write. There’s often a happy path, that defines what occurs if all goes well. There is usually also a path for each error that can occur.

You can also think about the paths a user may take in performing the story that needs to be split. For example, consider a sample story of paying for the items in a shopping cart, since that’s an example that would apply to any eCommerce site. In checking out, the buyer can select a shipping method--perhaps choosing between overnight delivery, two-day delivery, or a slower delivery.

Since choosing a shipping method will add to the effort to develop the story, consider leaving that functionality out of an initial implementation. Perhaps a first version assumes everyone gets slow delivery with no option for faster shipping. Developing just that path through the implementation simplifies the user interface (there’s no need to allow a user to select shipping options), reduces the number of cases to test, and so on. Splitting by path would be a very viable option in a situation like this.

As I mentioned at the start of this post, I’ve just released a video about splitting stories, and in it, I walk through a simple flowchart example to show one way of splitting a story using paths. To access the free video, simply sign-up here.

#3. Specifying the Solution as Part of the Story

A third mistake I often see when splitting stories is specifying the solution as part of the story. The best user stories will focus on what needs to be done rather than how it will be done.

For example, right now I have a picture I want to hang on my office wall. If I were to ask someone to do it for me, I could tell them how I want it done. I could say I want it hung using a ⅜” mushroom head toggle bolt. I’ve very much specified the how if I do that. Unless the exact details matter to me, I’d be better sticking to what I want: “I’d like this picture safely hung in about that spot on that wall.”

Including the solution within a story tends to happen when stories are being split too small. Once a story gets to a certain small size, there isn’t much more to say about the story and implementation details start to creep in when they shouldn’t.

For example, supposed we are building an Automated Teller Machine (ATM) to dispense. This is a classic example often given in software requirements books. It’s used to make the point that in specifying what’s needed in our new ATM we shouldn’t assume the ATM will use a PIN code and a card to authenticate a user just because that’s how we’ve always done it. After all, perhaps this time we’ll use a retina scanner.

Starting with a story that is simply “User authenticates him or herself” is a good idea and the how is left out of that story. But as that story is split further and further, eventually someone needs to say whether we’re using a retina scanner or traditional keypad and card reader. So, if you find your team including a lot of the specifics of how a story will be implemented, consider whether you are splitting stories such that they are smaller than they should be.

#4. Using a Spike on Every Story

A spike is an effort undertaken by a team to develop new knowledge rather than new functionality. Spikes are often used to reduce the risk or uncertainty on a story. If a team is unsure about or unfamiliar with a new technology, they may run a spike so that they can learn more about the technology.

Splitting a spike out of a story can be a good approach. It reduces the uncertainty in the initial story, which will likely make the story take less time to develop. But running a spike may also help a team and product owner discover new ways to better split the story if it’s still too large after the spike.

So, extracting a spike from a story is a good idea in some cases. But the mistake some teams will make is becoming over-reliant on spikes. Some teams will go so far as to split a spike out of every story.

Bad idea.

Spikes are most useful when a story includes an excessive amount of uncertainty, and when the team and product owner agree that uncertainty should be reduced before implementing the story. A spike should not be used when a story has an everyday, common amount of uncertainty.

Uncertainty exists to some extent in every story. Will users like this if done that way? Will this design perform adequately? Will this new tool perform as well as the vendor said it would? These, or ones like them, are questions that exist in every story. The goal of a spike should not be to eliminate all uncertainty. In most cases, that would be impossible anyway until the final line is written.

Instead, spikes should be reserved for when a user story contains so much uncertainty that starting the story in earnest would be a mistake without the knowledge to be gained from the spike.

Teams that split spikes out of stories too frequently often do so out out of fear of getting an estimate wrong. The team feels like they’ll be punished, or at least criticized, if a story takes longer to develop than they estimate. These teams are often found in cultures that confuse estimating with committing. To overcome this problem, either de-emphasize estimates or work to create safety around them so that teams don’t fear each estimate will used against them.

Spikes are also featured in the free video series. If you want a little more clarity around spikes, sign-up and watch the lesson here.

#5. Thinking All Business Rules Need to Be Enforced from the Start

Sometimes a user story is made difficult to implement because of rules the story must comply with. These are often called business rules because the business’s operation is usually the source of them. Other times, though, they can be thought of as rules imposed by the system. Let me illustrate this with an example.

Suppose you are on a team working at a bank that makes mortgage loans. Your team is developing a new mobile app that the bank’s customers will use to apply for home loans. Perhaps a rule in place at your bank is that no one can have more than $10 million in outstanding home loans. This rule applies whether the borrower wants one big loan or now wants a $6 million loan on a second home in addition to an existing $5 million loan.

Your team’s new mobile app will ideally enforce this maximum by not allowing a person to submit a loan application that would exceed $10 million in total loans (whether this is the borrower’s first, second or tenth loan).

A rule such as this will increase the effort to complete the user story because the new mobile app will need to look up the existing loan balance, add it to the requested loan amount and make sure the sum does not exceed $10 million.

If this rule makes the story take so long that it will not be feasible to implement the story within a single iteration, the rule should be relaxed (or removed) in the initial iteration and then added back in a subsequent iteration. And, no, the team shouldn’t release a product that violates business rules (temporarily).

The mistake I’ll see teams make is thinking that all such business rules need to implemented right from the start. This often leads a team and product owner to instead use a less desirable way of splitting the story.

In the next meeting in which you’re splitting stories, look for ways to partially implement a story by not supporting a rule initially. As long as you don’t intend to release that iteration’s finished work, you’ll find that relaxing rules can be a great way to split a story.

What to Do Next

Splitting stories is one of the most common challenges I hear about from teams. In this post I’ve covered five of the most common mistakes I see teams make and offered suggestions to overcome them.

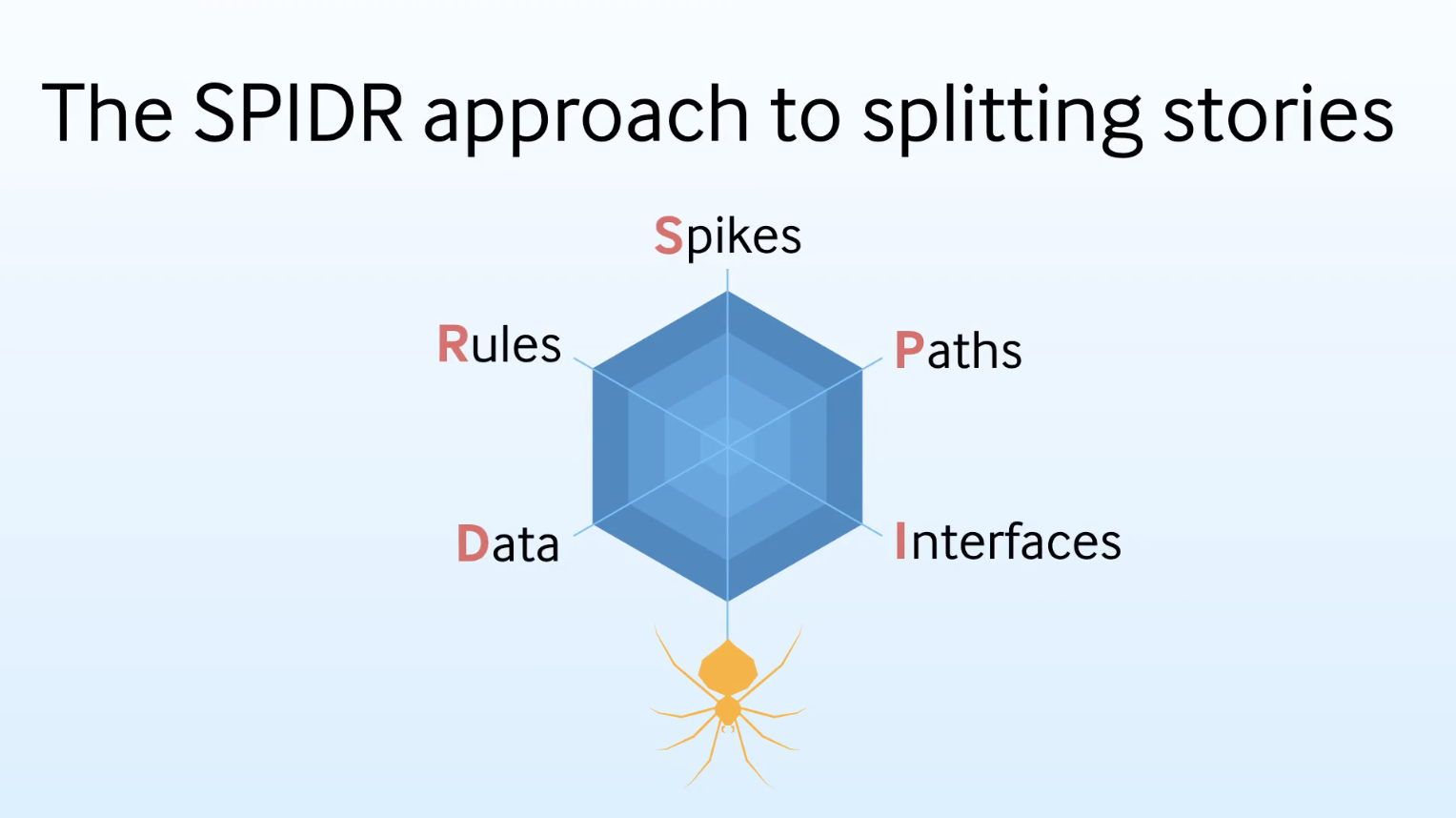

One of the best things you can do to avoid story-splitting mistakes is to become more adept at splitting stories. Fortunately, there are only five techniques you need to know that will enable you to split any story.

I mentioned three of the techniques in this post. They were splitting stories by

- Paths

- Rules

- Spikes

I didn’t have space to cover the other two techniques in this post; however, all five techniques are in the video released today as part of a free, four-part series I’m releasing on user stories. Click the button below to watch it now.

I want to watch a free video on the only five splitting techniques I’ll ever need

So if you’re like the majority of agile teams who struggle occasionally with splitting, go watch the video right now. I guarantee you’ll find it helpful.

Last update: June 25th, 2024