When I was young, my mom taught me to tie my shoes. I no longer remember the exact steps, but it had to do with bunny ears.

Since then I’ve learned there are many different ways to tie my shoes, many of which are better. Most are better for specific circumstances: wide feet, narrow feet, high arches, and so on.

Just as I’ve learned a lot since tying my first shoes, I’ve also learned a lot since working on my first agile teams.

Sprint Planning on Early Teams

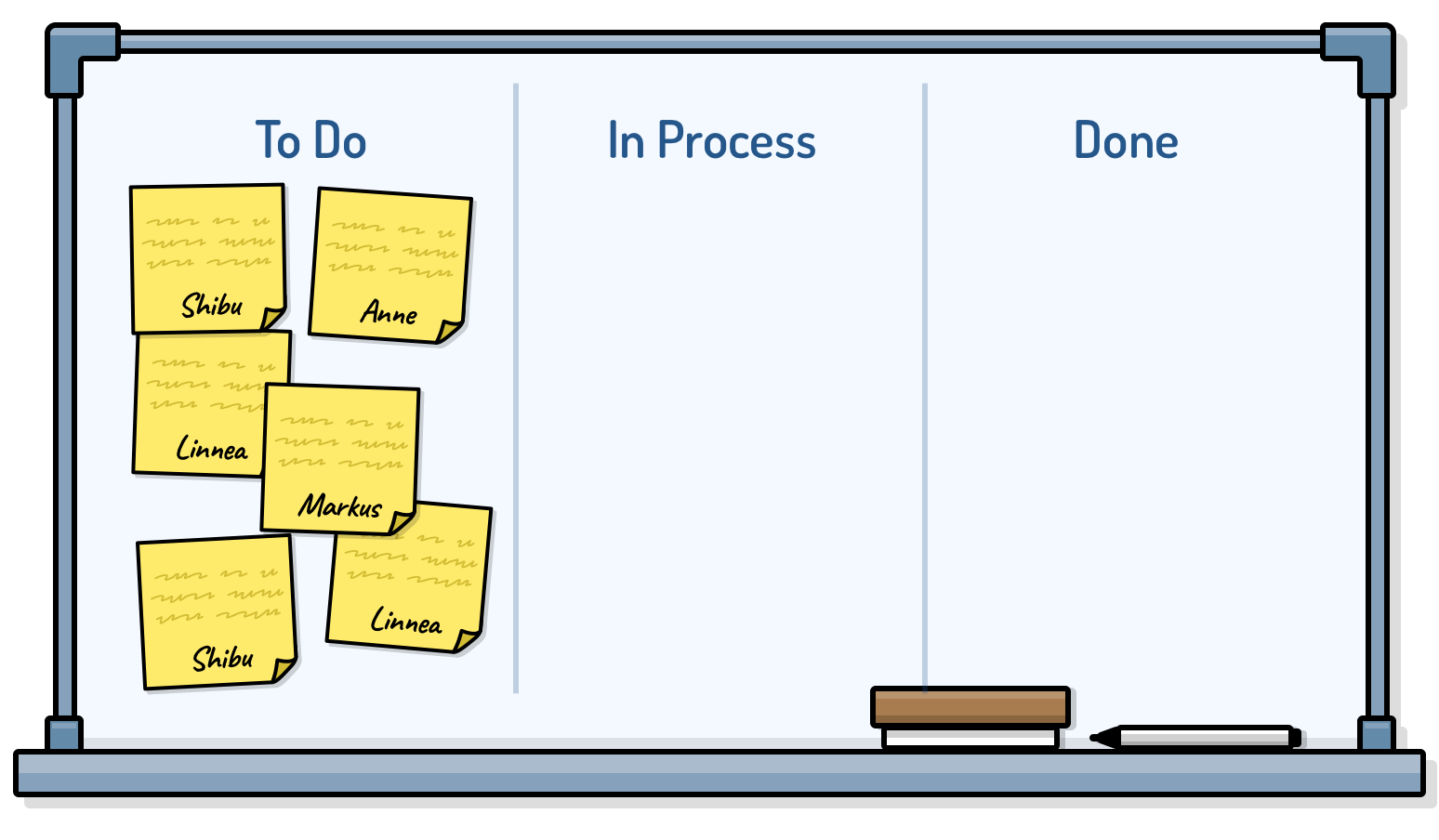

On my early agile projects, team members signed up for tasks during the sprint planning meeting. We would leave a planning meeting with someone’s name associated with each task. Our sprint backlog, which we called a sprint plan back then, looked like this.

There were some obvious advantages to this.

- It was incredibly clear who would be responsible for each task.

- Team members felt greater responsibility for their tasks.

- It helped the team see if anyone was overcommitted for the sprint.

The biggest drawback to the approach was that team members were making decisions about who would work on things when the least was known about that work. Many of my early teams ran four-week sprints. This meant they were deciding who would work on tasks that might start 20 days in the future. Obviously, quite a lot could change during those 20 days.

Moving Away from Signing up During Sprint Planning

I persisted with this approach for quite a while. I even advocated it in my User Stories Applied book, which was published in 2004.

But, just as with tying shoelaces, I learned there was a better way. Rather than having team members sign up for every task during sprint planning, I learned it was better to have team members choose their next tasks as the team progressed through the sprint.

Usually this would happen during daily standup meetings. As team members reported they had finished one task, they’d select their next task.

This works really well. Decisions about what to work on next can consider the full state of the iteration. Questions such as these could be considered:

- Is the team behind on a certain product backlog item?

- Is the sprint goal at risk?

- Is one type of work (e.g., testing) falling behind?

There Was a Problem

This real-time allocation of work really helped. Teams that used this approach were better able to adjust as things changed during an iteration.

There was just one problem: During sprint planning, how could a team know if anyone was taking on too much work?

This had been easy to assess when all tasks were allocated to individuals during sprint planning. Each team member could look at the set of tasks they were taking on and decide whether it was neither too much nor too little but just right.

But when tasks weren’t allocated during sprint planning, that assessment was impossible.

Finding a Path Through the Work

Without a name next to every identified task, teams found it harder to decide whether they were bringing the right amount of work into the sprint.

To better assess the amount of work being brought into the sprint, I began asking teams to “find a path through the work.” Think of this as team members each pointing to the set of tasks they thought they’d work on during the sprint. For example, you point to four tasks you anticipate doing. I point to a different four. And our remaining team member points to the other three.

If every task has someone saying “I’ll do it” and if no team member feels overloaded with work, the selected work is most likely achievable.

When team members “found a path through the work,” it was just one of multiple possible paths. Team members were not expected to do exactly the tasks they’d indicated. Rather, there simply needed to be at least one possible path through the work for everyone to feel the sprint was well planned.

To promote the transient nature of this tentative allocation of work, some teams referred to this as “signing up in pencil.” In pointing at a set of tasks and saying, “I intend to do these,” team members were signing up, but in pencil that was metaphorically erased at the end of the meeting, leaving each task without being officially allocated to anyone.

Estimating Without Knowing Who Would Do Each Task

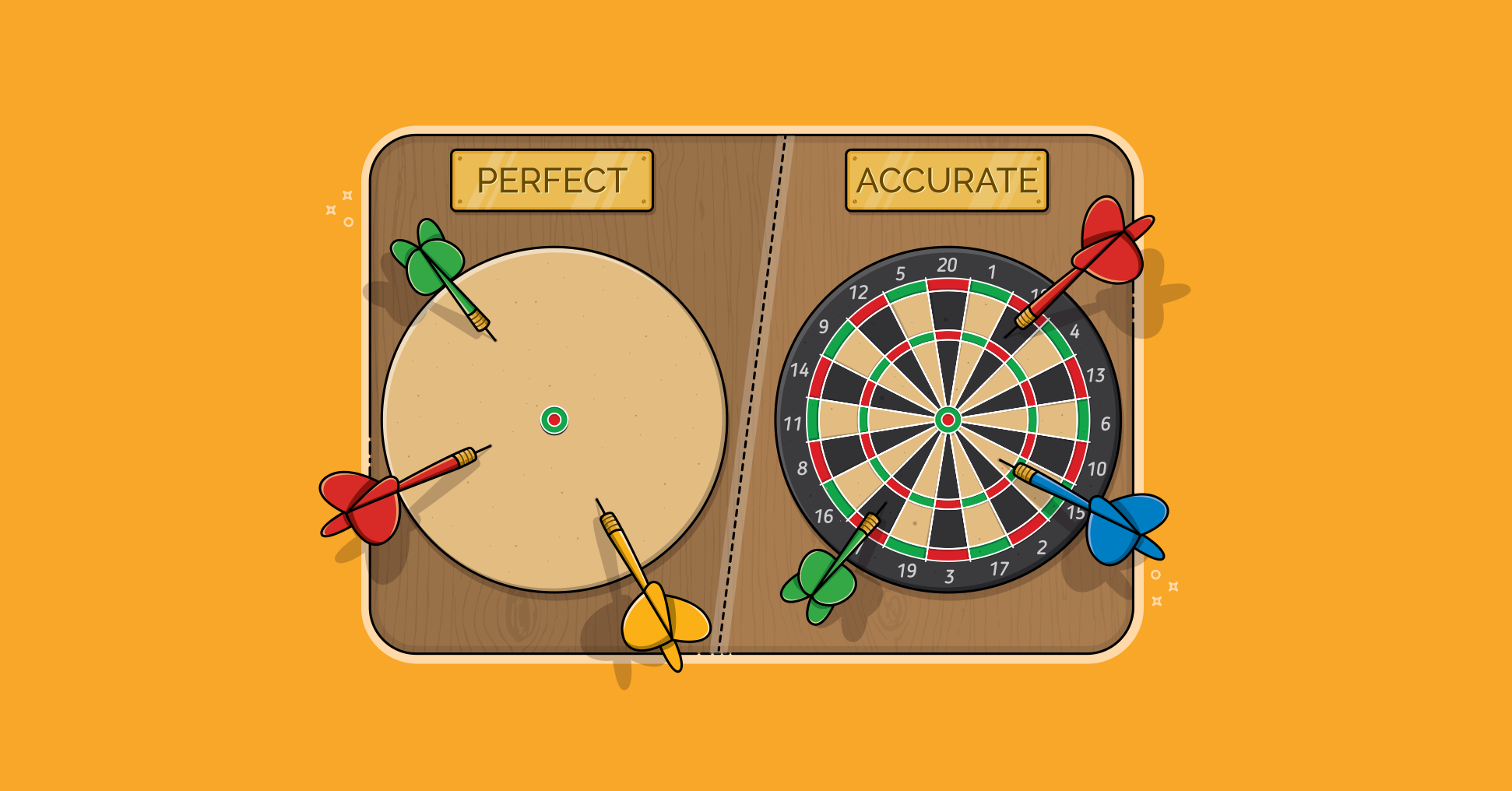

An additional problem these teams faced was estimating how long a task would take without a specific person allocated to the task. What estimate should be put on a task that will take either 5 or 10 hours depending on which team member does it?

The idea of signing up in pencil helped here, too. The estimate put on a task could be the estimate for how long the work would take for the person stating an intent to perform the work.

So, your estimates go on the tasks you think you’ll do and my estimates go on those I think I’ll do.

Then, during the iteration, when someone started a task they would change the estimate at the moment they grabbed that task as their next. In that way I might grab a task and immediately change its estimate from 5 to 8 hours if I’m slower at that work than the person who had originally planned to do the work.

This approach works because it usually represents just a swap of hours between team members. You grab a task I’d intended to work on and change my estimate. And I grab a task you’d planned to do and change yours.

And even if the new estimates are higher, the current allocation of work is always expected to represent the best, currently knowable path through the work. In other words, team members are seeking the optimal path through all that needs to be done in an iteration.

What I Currently Recommend

I’m a big fan of delaying the decision about who will work on something until closer to when the work begins. And so I prefer not allocating all tasks during sprint planning. Members of teams I coach will usually each sign up for just their first task at the end of sprint planning. That allows everyone to leave a sprint planning meeting knowing exactly what work to begin.

While I prefer not allocating all tasks during sprint planning, I think there are two cases in which a team can benefit from signing up for every task during sprint planning:

- Teams that are new to agile

- Teams that struggle with individual accountability

Individual and Team Accountability

As noted earlier, when team members sign up for tasks they feel a greater sense of individual accountability toward those tasks with their names on them. Seeing my name next to a particular task will make it more likely I complete the work on that task.

But this comes at the expense of team accountability. I feel more accountable for tasks with my name on them but less accountable for those with your name.

A team will be at its best with a strong sense of team accountability (everyone is accountable for all the work). But it’s hard to create team accountability without having individual accountability first.

So if there is a low sense of individual accountability on your current team, you may want to allocate all the tasks in sprint planning for a while. Once individual accountability has increased, consider not allocating every task during sprint planning and shifting toward feelings of team accountability.

Teams that Are New to Agile

Teams that are new to agile may also benefit from allocating all tasks during sprint planning for a while. When the close collaboration of agile is new to a team, it can be hard to imagine how a team can commit to finishing a set of work without first divvying up all work among team members.

An Easy, Hybrid Way to Get Started

For any team that wishes to move away from assigning all tasks during sprint planning, there is fortunately an easy way of making the shift. Do so by gradually reducing the number of tasks that are allocated to specific people during the planning meeting.

If your team allocates all work today, try allocating only 50% of the tasks next time. Team members would then walk out of the next planning meeting with, say, 5 tasks instead of 10. The remaining tasks—about half the work of the sprint—are not yet allocated to team members. Those tasks will be allocated as the sprint progresses.

I feel comfortable almost guaranteeing that this will feel no better or no worse to the team. But it’s a good step in the direction of minimal allocating. So have the team allocate half of the work for a couple of sprints.

Do it until the team becomes comfortable with the idea. And then dial it up. Instead of allocating 50% of the tasks during the planning meeting, allocate only 25%. Do that a few times until everyone is again comfortable with the approach.

Next, go further. Allocate only about 10% of tasks during the planning meeting. And finally consider going all the way. Even then, most teams will have each team member sign up for the one or two tasks they do immediately after the planning meeting.

What Do You Do?

As we gain experience, we find new and better ways of working. Just as I outgrew tying my shoes by thinking about bunny ears, teams I coach shift away from allocating tasks during sprint planning as those teams gain experience.

Last update: July 15th, 2024