People resist changing to Scrum for many different reasons. Some may resist because they are comfortable with their current work and colleagues. It has taken years to get to their current levels in the organization, to be on this team, to work for that manager, or to know exactly how to do their jobs each day. Others may resist changing to Scrum because of a fear of the unknown. “Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t” is their mantra. Still others may resist due to a genuine dislike or distrust of the Scrum approach. They may be convinced that building complex products iteratively without significant up-front design will lead to disaster.

Just as there are many reasons why some people will resist Scrum, there are many ways someone might resist. One person may resist with well-reasoned logic and fierce arguments. Another may resist by quietly sabotaging the change effort. Still another may resist by quietly ignoring the change, working the old way as much as possible, and waiting for the next change du jour to come along and sweep Scrum away.

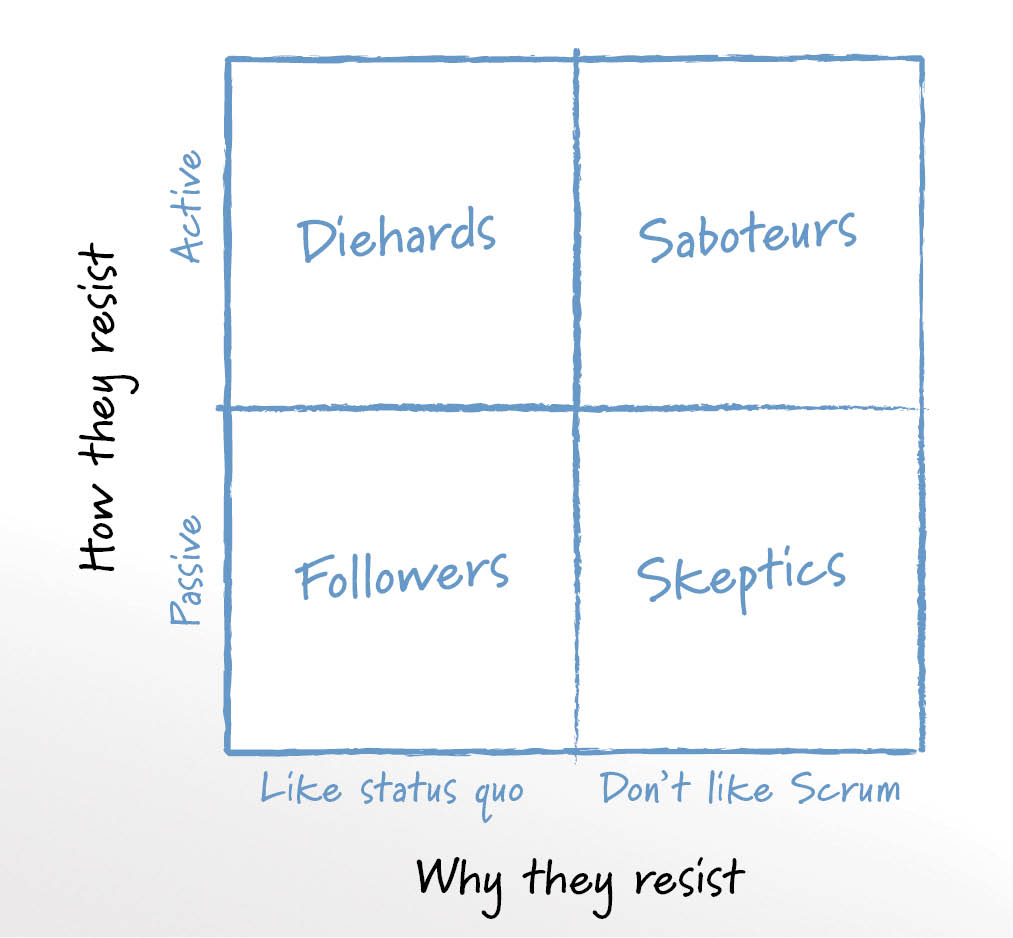

Each act of resistance carries with it information about how people feel about adopting Scrum. As a change agent or leader in the organization, your goal should be to understand the root cause of an individual’s resistance, learn from it, and then help the person overcome it. There are many techniques you can use for doing this. But unless the technique is carefully chosen, it is unlikely to have the desired effect. To help select the right technique, I find it useful to think about how and why someone is resisting. We can group the reasons why someone is resisting Scrum into two general categories:

- They like the status quo.

- They don’t like Scrum.

Reasons for resistance fall into the first category if they are actually a defense of the current approach. This type of resistance to changing to Scrum would likely result no matter what type of change was being contemplated. Reasons fall into the second category if they are arguments against the specific implications of beginning to work in an agile manner.

Categorizing how individuals resist is even simpler: Is the resistance active or passive? Active resistance occurs when someone takes a specific action intended to impede or derail the transition to Scrum. Passive resistance occurs when someone fails to take a specific action, usually after saying he will.

The figure below combines the whys and hows of resistance into four general types of resistance, each with a name descriptive of the person who resists in the way indicated by the labels on the axes.

A skeptic is someone who does not agree with the principles or practices of Scrum but who only passively resists the transition. Skeptics are the ones who politely argue against Scrum, forget to attend the daily scrum a little too often, and so on. I am referring here to individuals who are truly trying to stop the transition, not people with the healthy attitude of “this sounds different from anything I’ve done before but I’m intrigued. Let’s give it a try and see if it works.”

Shown above the skeptics are the saboteurs. Like skeptics, saboteurs resist the transition more from a dislike of Scrum than support for whatever software development process exists currently. Unlike a skeptic, a saboteur provides active resistance by trying to undermine the transition effort, perhaps by continuing to write lengthy up-front design documents, and so on.

On the left side of the figure are those who resist because they like the status quo. They are comfortable with their current activities, prestige, and coworkers. In principle, these individuals may not be opposed to Scrum; they are, however, opposed to any change that puts their current situation at risk. Those who like the status quo and who actively resist changing from it are known as diehards. They often attempt to prevent the transition by rallying others to their cause.

The bottom left of the figure shows the followers, who like the status quo and resist changing from it passively. Followers are usually not enraged by the prospect of change, so they do little more than hope it passes like a fad. They need to be shown that Scrum has become the new status quo.

When introducing a complex change into a large organization, resistance will be inevitable. What isn’t inevitable is the reaction of an organization’s leaders to that resistance. In a 1969 Harvard Business Review article, Paul Lawrence describes an appropriate response to resistance.

When resistance does appear, it should not be thought of as something to be overcome. Instead, it can best be thought of as a useful red flag—a signal that something is going wrong....Therefore, when resistance appears, it is time to listen carefully to find out what the trouble is. What is needed is not a long harangue on the logics of the new recommendations but a careful exploration of the difficulty.

While its important to confront resistance, be careful not to create an atmosphere of “us” against “them.” The real goal is to create a feeling that the transition to Scrum is inevitable and that, as the Borg of Star Trek taught us, “resistance is futile.” The need to foster this atmosphere does not give you carte blanche to ignore the feelings and reactions of employees or to steamroll Scrum into an organization. Instead, to paraphrase Nigel Nicholson in a 2003 article for the Harvard Business Review, when an employee resists, an effective leader looks at the employee not as a problem to be solved but as a person to be understood.

For more help with overcoming obstacles to your agile transition, see Chapter 6 of Succeeding with Agile.

Last update: April 25th, 2023