I have no problem with a decision maker asking an agile team to estimate how long it will take to deliver a product, even if the product backlog has a huge number of product backlog items. There could be hundreds or even thousands of items, and I'd have no issue with someone asking for an estimate.

I will be happy to provide leadership with that information, as long as leadership understands that information has a cost.

I don’t mean someone has to slip the team a $20 tip. What I’m referring to is the time the team will spend creating that estimate.

The More Precise the Estimate, The Higher the Cost

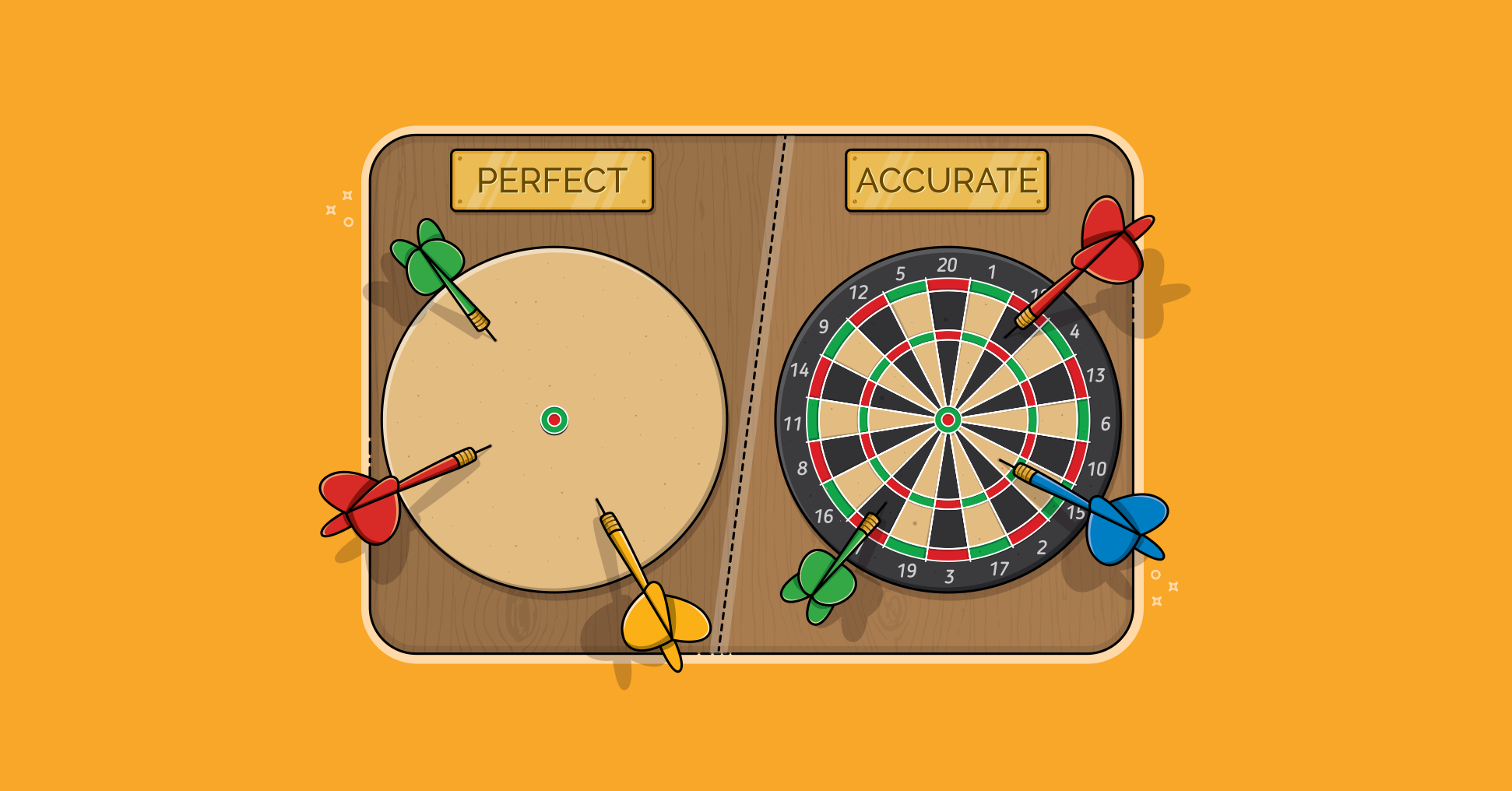

If a decision maker wants a really quick, down-and-dirty agile estimate of when a set of features will be done, I can answer that instantly and accurately. My answer? In the future.

But while that answer is certainly accurate, it’s probably not what leadership is looking for. (And don’t blame me if you get fired for trying that answer!)

Most times, leadership needs to have a rough idea of when a product will be delivered. So the team puts more effort into estimating and thinks harder about what’s being asked for. They may come up with something like, “Three to six months.” That’s certainly better than “in the future.” And often, it’s good enough for decisions like, “Should we start this project?” and, “Should we add more teams?”

But, many decision makers will insist on something more precise—perhaps an answer like, “In August.” Note that giving leadership a specific month is still framing your estimate as a range, which is vital to giving an accurate estimate. But, it’s much more precise than saying, “Three to six months.”

To add precision to an estimate requires time. And that is the cost I’m referring to.

What to Do When Asked for a Precise Estimate

As long as leadership is willing to pay that cost, a good Scrum team should be willing to provide detailed and precise estimates. The problem comes when someone wants a highly precise estimate and isn’t willing to pay the cost, for example, “I need to know by lunch time today exactly when this large project can be delivered.”

When asked to provide an estimate at a level of precision you’d prefer not to provide, do not argue that a precise estimate is unnecessary. That will usually get you nowhere. Instead take the attitude that you’re happy to provide the estimate (even if you aren’t), but challenge how precise or detailed the estimate needs to be.

If providing the estimate will cause all other work to stop for a week, leadership needs to understand that. If someone has a true need for a precise estimate, they may be willing to let all other work stop. If, on the other hand, they just wants a precise estimate to feel good or to hold the team accountable, they will probably settle for an easier-to-provide but less precise estimate.

Information has a cost. If the person asking for that information is willing to pay that cost, you need to be willing to provide the information.

Last update: April 9th, 2024