Starting the start of the industrial revolution in 18th century, there has been a trend of increasing specialization. Rather than workers being involved in all aspects of creating a product, workers began to produce smaller and smaller subsets of the product. By the time Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations in 1776, pin-making had become specialized to the point where it could involve eighteen different specialists. Smith wrote that, "One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head..."

Not only has this trend continued through the present day, it is likely accelerating. A recent article in Harvard Business Review, "The Age of Hyperspecialization", claims that as work becomes more knowledge-based and as communication technology improves, it is easier to split work into smaller and smaller pieces. The article talks about about a number of companies and business models. But, in particular, presents a site called TopCoder, which allows companies to present development work that needs to be done.

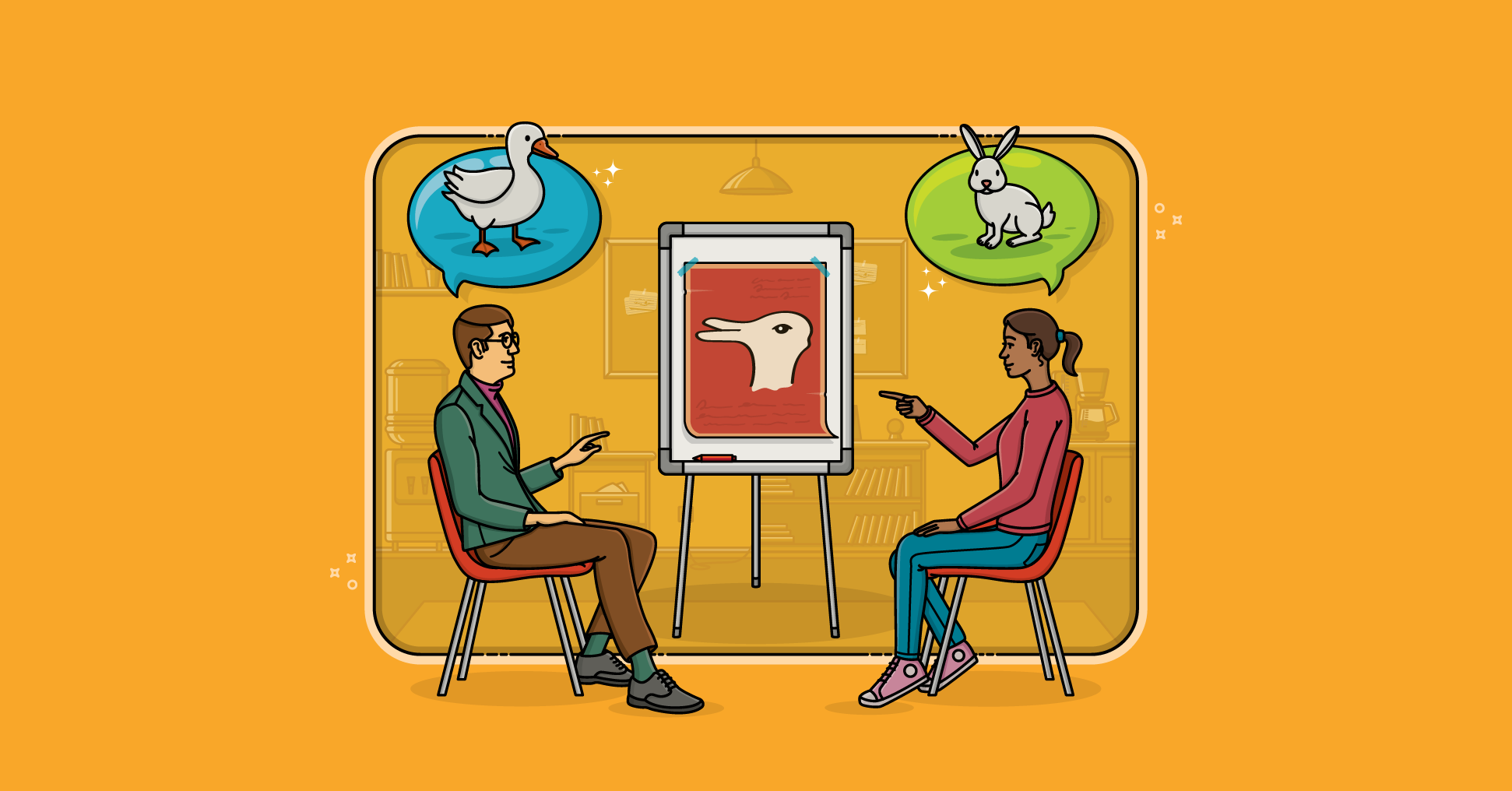

The work is then bid on and completed by hyperspecialists all over the world: a designer in the US, an analyst in Kiev, an architect in Bangalore, a programmer in Beijing, and so on. These individuals do not work together as a team. Rather they have very specific artifacts to produce. The artifacts are defined in a very sequential ("waterfall") process. It is interesting to think about a grand, sweeping trend like the one toward hyperspecialization in contrast to agile development.

Agile does not at all require individuals to be generalists, but individuals are expected to work together as a team. The handoff-driven model created by hyperspecialization and used on sites like TopCoder are anything but agile. So where does this go? Is agile at odds with a 300-year trend? It could be. Or, perhaps teams will evolve more agile ways of working within the trend toward hyperspcialization.

Last update: April 13th, 2022